Book Review

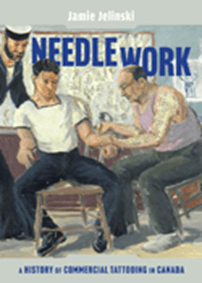

Needle Work: A History of Commercial Tattooing in Canada, 2024

By Jamie Jelinski

Buy the book: https://www.mqup.ca/needle-work-products-9780228021988.php

Is tattooing art or commerce? In a new book, Jelinski argues both: tattooing is a line of work and “a job like another,” but it is also one that is simultaneously commercial and creative (12, 13). Describing his subjects as “for profit image producers . . . who received an income for rendering tattoos on a regular basis,” Jelinski locates tattooists among the growing numbers of Canadians earning a living by producing images and visual culture for profit (4, 22). The story he tells is largely chronological, tracing evolving operating practices, technologies, and stylistic trends as tattooing moved from the margins towards the mainstream of middle-class respectability.

Tattooing historiography has largely neglected those who tattoo for a living, and the availability of sources plays a significant role in dictating the shape of this account (37). Most tattoos, like the body itself, change over time, eventually disappearing from view after death. Much of the documentation available about tattoos in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries record tattoos on the bodies of Indigenous peoples, criminals, and military personnel; that is, on people whose bodies were subject to surveillance by anthropologists, travellers, and criminologists, deepening the association of tattooing with primitives, outsiders, and rough populations. Insofar as the majority of tattooers “maintained…quiet, regular lives and work habits.” Needle Work relies heavily on sources left by exceptions and outliers, both those “who helped create their own criminal records” and those who developed relationships with artists and galleries in the conventional art world (37-38).

Jelinski scoured legal records and daily papers for clues, and examines how tattooists represented themselves in images, advertisements, media interviews, and personal recollections. Evocative images that include yellowing sheets of well-used “flash” (simple line tattoo stencils), reproductions of business cards, and black and white photos of storefronts and tattooers at work illustrate the evolution of tattooing in addition to creating a wonderful sense of intimacy.

Beginning in the late-nineteenth century, Needle Work traces the trajectory of commercial tattooing from rough trade to small business, stopping in the late 20 th century just as the dramatic expansion of tattooing was underway. Tattooers operated primarily as itinerants until the mid-1950s, moving frequently to find new customers and “the personal freedom to live their lives and conduct their work where, when, and how they saw fit” (25). Most tattooers in these early decades were self-taught. Working in carnivals and amusement arcades with minimal equipment, they applied simple line “flash” tattoos using standardized stencils. The stigma of marginality affected those who gave tattoos as well as those who received them and was reinforced by the places where tattoos were received.

Through mid-century, many tattooists transitioned to fixed premises that included rented spaces in barber shops, leased storefronts, and semi-permanent home businesses. As their visibility increased, tattooers came under the scrutiny of expanding municipal governments, often through sensational articles in daily papers that amplified the moral and health concerns circulating around tattooing. Diverse municipalities across Canada introduced legislation to regulate tattooing. Jelinski shows that regulations ultimately worked to the benefits of tattooers, contributing a sense of legitimacy and respectability. Business cards and photographs of tattoo studios began to emphasize personas of professionalism with tattooers adopting designations of “professor” and “doc,” donning lab coats, and upgrading business premises. New locations, greater attention to hygiene, and a professional demeanor assuaged tattoo anxiety, especially among women who tattooers claimed made up a growing share of their clientele.

The benefits of fixed locations included greater stability in work and in personal life, attracting more operators as well as more clients. Improvements in tattooing machinery lowered costs, lessened pain, and opened the way to aesthetic innovations. The customer base continued to broaden as tattoos become more common and accepted in some workplaces. Artistry improved: by the late 1970s, images were more varied and colourful, with an increased sense of dimensionality. Tattoo shops offered a wider range of styles and services, including custom designs and tattoo removal. The later chapters focus on the handful of tattooers who gained a degree of acceptance in the conventional art community, forming relationships with artists and galleries, although primarily those situated on the periphery of Canada’s dominant cultural institutions. A brief epilogue takes the story into 1990s and increasing mainstream acceptance, epitomized by tattoo conventions in upscale urban hotels.

Focused on the personhood of tattooers, Needle Works tells many interesting stories, but as business history it would have benefitted from a broader framework of analysis. Focused on tattooists as producers of visual images, Jelinski also overlooks connections to recent research in small business history exploring marginalized entrepreneurs. Canadian tattooists faced similar challenges to African American proprietors and counter-culture activist entrepreneurs: social stigma, legal constraints, lack of experience, and limited capital. [1]

Moreover, all of these independent “entrepreneurs on the margins” seem to think about their businesses in ways other than profit maximization, gauging success by their ability to secure a livelihood, mentor apprentices, build community, and foster broader acceptance of their products, craft, and culture. Comparison with other, similarly marginalized businesses also illuminates interesting differences, beginning with the connection between price and demand. While flash tattoos were affordable for the majority of working-class individuals until the advent of customization in the 1970s, higher prices going forward actually correlated with increasing, rather than decreasing demand. The ability to craft more elaborate, personalized, and artful work opened new markets.

Greater attention to context, particularly to changes in social and cultural conventions that accelerated demand, would have enriched our understanding of tattooing’s commercial development. Steady, incremental changes in business practices (cheaper, faster, regulated, less painful, and more artistic) blunted the stigma of tattooing as a rough trade but are insufficient to explain the dramatic upswing in demand already underway by the final years of the study. The normalization of tattoos and the growth of the tattoo sector were aspects of profound social and cultural shifts eroding historical constraints and negative perceptions after the second world war. Religious prohibitions lost power as society became increasingly secular, and racist and colonial attitudes that associated tattoos with primitivism declined. Tattoos gained traction as emblems of rebellion and non-conformity in the 1950s and 1960s.

Acceptance continued to grow as hostility to counterculture movements lessened and appreciation increased for working-class, tribal, and Asian cultures where tattooing was more common. Visual images became more important as the mass media evolved. Changes in fashion and shifts in the geography of settlement to warmer climates exposed more skin. Body modification emerged as a cultural phenomenon and a rapidly growing commercial sector that included diet fads, tanning, body building, piercings, and cosmetic surgery as well as tattoos. By the late 20th century, tattoos were widely accepted and appreciated as a form of body art and acts of creative self-expression, transcending earlier associations with deviancy and lower social status, and increasing opportunities for income earning and artistic recognition.

As paid work, tattooing transitioned with success from the margins towards the mainstream. Jelinski shows that even as demand grew, Canadian tattooists remained predominantly small businesspeople, operating as niche providers of specialized services not readily available in mainstream retail settings. The application of tattoos remained an intimate exercise, one that required specific technical skills and a degree of artistic talent, carried out in local shops. But while tattooing itself resisted mass production and distribution, growing demand for and fascination with tattooing opened the way to larger profits. Corporate enterprises emerged in adjacent sectors, generating significant revenue and employment as suppliers of equipment, ink, and images, and new products and services ranging from tattoo removal to the manufacture and distribution of temporary tattoos. Tattoos and tattoo artists are featured on cable tv, magazines, websites, and social media. Celebrities popularize tattoos and leverage lingering associations with counterculture to enhance their personal brand.

Looking at the evolution of commercial tattooing as part of a larger dynamic rather than incremental changes within the tattoo sector, it is apparent that customization and commodification have been mutually reinforcing. Customization transformed both the experience and the product. Most obviously, more intricate and expensive tattoos display economic power. But more importantly, customization transformed tattooing into a more collaborative practice involving discussion and design development between client and artist, affording those getting a tattoo as well as the artist giving the tattoo opportunities for creative self-expression.

For many people getting a tattoo became an act of individual storytelling, often commemorating significant life events. Tattoos are seen as a medium for healing and the decision to get a tattoo can be a therapeutic exercise whereby individuals actively reimagine and reconstruct their physical and physic identities. As tattooing became more mainstream, it became simultaneously more personalized and more commercialized, expanding market opportunities for individual tattooists and corporate capitalism.

Needle Work, itself an artefact of the growing interest in tattooing, is an interesting read and a good beginning. However, much of the story still remains to be told. [2]

- 1

For useful comparisons that expand the understanding of tattooists as entrepreneurs on the margins, see Joshua Clark Davis, From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017) and Ronny Regev, “The National Negro Business League and the Economic Life of Black Entrepreneurs,” Past & Present 262 (February 2024): 207-241.

- 2

Recent studies in tattooing history that pay particular attention to culture and commerce include: Deborah Davidson, ed., The Tattoo Project: Commemorative Tattoos, Visual Culture, and the Digital Archive (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2017); Margot DeMello, Bodies of Inscription. A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000); Sinah Theres Klos, ed., Tattoo Histories: Transcultural Perspectives on the Narratives, Practices, and Representations of Tattooing (New York and London: Routledge: 2020); Lars Krutak and Aaron Deter-Wolf, eds., Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing (Seattle, The University of Washington Press, 2018); Matt Lodder, “The myths of modern primitivism,” European Journal of American Culture 30, No. 2 (2011): 99 – 111; Matt Lodder, Tattoos: The Untold History of a Modern Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024); Michael Rees, “From Outsider to Established - Explaining the Current Popularity and Acceptability of Tattooing,” Historical Social Research, 41, No. 3 (2016): 157-174. On today’s tattoo industry, see Fortune Business Insights, “Tattoo Market Size, Share & Industry Analysis, By Type (Temporary and Permanent), By Category (Cosmetic, Medical, and Professional), By Application (Skin, Corneal, Mouth, and Others), By End-user (Women and Men), and Regional Forecast, 2024-2032,” October 14, 2024, https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/tattoo-market-104434

Dr. Bettina Liverant

University of Calgary