Book Review

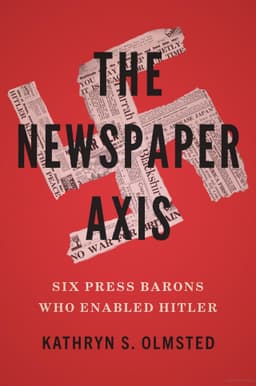

The Newspaper Axis: Six Newspaper Barons Who Enabled Hitler, 2022

By Kathryn S. Olmsted

Buy the book: https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300256420/the-newspaper-axis/

One of the hallmarks of scholarship on Anglo-American journalism history of the past century is a focus on the admirable. Many historians trace the developments of professional ethics in reporting, the shouldering of public responsibility by publishers and journalists, and the disengagement of newspapers from involvement in party politics. Many works in journalism history are accounts of good journalism. From the perspective of business history, the story is rather different and more inclusive of some wildly popular but ethically dubious newspapers like the New York Daily News and the Daily Mail, two of the main subjects of Kathryn Olmsted’s The Newspaper Axis. On both sides of the Atlantic, the most commercially successful publishers were not those at the forefront of newspaper trends preaching public service and good journalism but rather those who did quite the opposite. The early twentieth-century publishers who developed strategies to cultivate the widest possible readership, and thus the highest advertising revenues, were in many respects extensions of nineteenth century publishing, and across this span many newspapers were clearly understood to reflect the prejudices of their owners. The Newspaper Axis is a welcome addition to a growing collection of works that are challenging some long-held assumptions about the press and developing a new business and political history of newspapers focusing on the publications that became popular and successful while remaining overtly biased. Through works like Olmsted’s, scholars are starting to develop a more complete portrait of the richness, messiness, and occasional darkness of the public sphere that newspapers shaped.

The Newspaper Axis focuses on six publishers: British Lord Rothermere, the expatriate Canadian Lord Beaverbrook, and the Americans William Randolph Hearst, Robert McCormick, and siblings Joseph and Cissy Patterson. These publishers were all commercially successful, and in the 1930s and 1940s their nationalist and non-interventionist perspectives were coordinated in various ways. Three of the four Americans in this book were cousins, and there were regular private conversations among all six of these publishers, something that Olmstead traces effectively with archival research. In different ways, each publisher built upon a foundation of interwar isolationism to promote Hitler and discourage intervention in geopolitical developments in continental Europe. Hearst will be well known to most readers of The Newspaper Axis, McCormick rather less so, and the Patterson siblings even less. Rothermere and Beaverbrook are prominent in the historiography of British journalism but not often considered in comparison to their American counterparts. All six publishers ran highly successful publications, and indeed Rothermere and Joseph Patterson published the highest circulating newspapers in Britain and the United States.

The malignant aspect of this commercial success, as Olmsted shows, was that all these papers profited from political stances that in some way supported and enabled Nazi Germany. Not all the publishers in The Newspaper Axis came from privileged backgrounds, but each came to live in extreme privilege thanks to their newspapers, all of which expressed some degree of fascist sympathy. Their politics varied from Rothermere’s overt enthusiasm for Hitler to Joseph Patterson’s idiosyncratic pro-New Deal anti-interventionism. But, taken together, these six publishers “pressured their nations’ leaders to ignore the menace of fascism.”(2)

Like Father Charles Coughlin on the American airwaves, these publishers provided readers with a steady stream of assertive and occasionally angry nationalism. One of the powerful lessons of The Newspaper Axis is that their newspapers in avoiding the frothy quality of Coughlin’s broadcasts created an even more insidious and influential support for fascism by normalizing and even celebrating dictatorial conduct as effective leadership, as Rothermere’s Daily Mail consistently did with Hitler in the mid-1930s. In the US, Hearst published growing praise for Hitler, and he also printed columns written by the German leader and Mussolini. In the 1930s, Olmsted writes, “by giving fascist dictators direct access to the American public and allowing them to present themselves as peace-loving, tolerant champions of order, Hearst helped to normalize them for his 30 million readers.”(50)

The stakes of being non-interventionist changed after 1939 for British publishers, and after 1941 for their American counterparts. But even after each country entered the war, Olmstead shows, support for it in the publications in The Newspaper Axis remained irregular and incomplete. Disturbingly, one of the common themes in these newspapers before and during the war was a palpable prejudice against Jews. If these six Anglo-American publishers failed in their project of opposing military action against Nazi Germany, one important element of their project to enable Hitler did persist, and that was a pervasive promotion of anti-Semitism. In countless editorials and biased news reports, Olmsted demonstrates, these six publishers demonstrated “how much their determination to ignore or appease Hitler was informed by anti-Semitism.”(142-143) That element of their moral shortcoming would remain an important and troubling part of Anglo- American political culture after the war.

Overall, The Newspaper Axis is a compelling, sobering, and incisive account of the politics of some of the most successful British and American newspapers of the 1930s and 1940s. It is a welcome addition to a historiography of journalism that is becoming more comparative and more inclusive of the commercially successful newspapers that were not part of the move toward dispassionate and objective reporting. In this regard, it would have been interesting to read more about what historians can learn from these six publishers to rethink some of the dominant prevailing trends in the field. There is little reflection here on the broader historiography, and the connections in the brief epilogue to subsequent media figures like Clarence Manion and Rupert Murdoch are sketchy and suggestive. But still, this is an important, insightful, and well- researched book about a powerful but understudied group of Anglo-American publishers, and about the ways that media institutions, which we assume in liberal societies to be foundations of democracy, can occasionally and influentially act contrary to those assumptions.

Michael Stamm

Michigan State University